Environmental Impact Certificates: Financial Barriers, Data Realities, and the Quiet Intelligence of Community Projects

By Diego Rivera, Niña Cerilla, & Nurfatin Hamzah

A note on naming: “Ecocerts” is rebranding to “Bumicerts” due to trademark considerations. “Bumi” means “earth” in Indonesian and Malay, reflecting our commitment to centering the voices and landscapes of communities across the global majority.

Why Bumicerts Exist

Bumicerts began as an attempt to make biodiversity documentation accessible to small Indigenous and local groups doing ecological restoration. This need exists because global environmental certification systems are built at scales and costs that automatically exclude the communities doing most of the world’s nature stewardship.

The problem is threefold. First, certification is expensive - forest restoration projects must spend thousands on auditors and baseline studies before documenting impact. Second, existing approaches rely on incomplete, Global North-skewed data that undervalue the stewardship practices and ecological knowledge of communities in the global majority. Third, even when communities prove their work, connecting with funders means navigating systems designed for large-scale projects, not small teams in remote landscapes.

Impact certification systems treat ecological outcomes as fungible units. Meanwhile, communities see ecosystems as living relationships that can’t merely be measured in numbers. Bumicerts was our attempt to flip that script.

Between February and November 2025, 46 projects showcased their impact through the Bumicerts marketplace (previously Ecocertain). They ranged from agroforestry and mangrove restoration to regenerative farming, women’s empowerment and climate education. Each project uploaded “proof of work” they had at hand - whether that’s geotagged trees, photos and videos during implementation, impact reports, and so on.

Looking across 148 community claims and qualitative submissions using BroadListening - an in-house technology that analyzes community voices at scale, identifies themes and claims, and presents results interactively - we’ve mapped Bumicerts into seven broad environmental domains:

Agroforestry

Mangrove restoration

Reforestation and tree planting

Sustainable agriculture

Water and soil

Biodiversity and conservation

Social dimensions, such as women’s leadership and youth education

On paper, this diversity is a strength. It shows that communities are doing much more than planting trees. They are rebuilding relationships between people, land, water, and livelihoods. In practice, the diversity comes with a cost. The more heterogeneous the projects become, the harder it is for a rigid, single-metric certification system to evaluate them fairly.

The evidences they submitted followed a similar pattern:

Around 65% provided low-depth evidence: one or two photos, a broken link, a short description.

About 25% reached medium depth: multiple photos, videos, some narrative.

Roughly 10% offered high-depth documentation: geodata, monitoring reports or structured datasets.

Many of the low-depth submissions came from groups working with limited connectivity, no dedicated data staff and almost no support for building documentation practices. This made visible that common expectations for “good evidence” quietly assume access to time, tools and infrastructure that many local initiatives simply don’t have. Communities are not waiting for a standard to tell them what to do. They already document their work. The real question is whether our systems know how to read what they’re saying.

What the Numbers Say

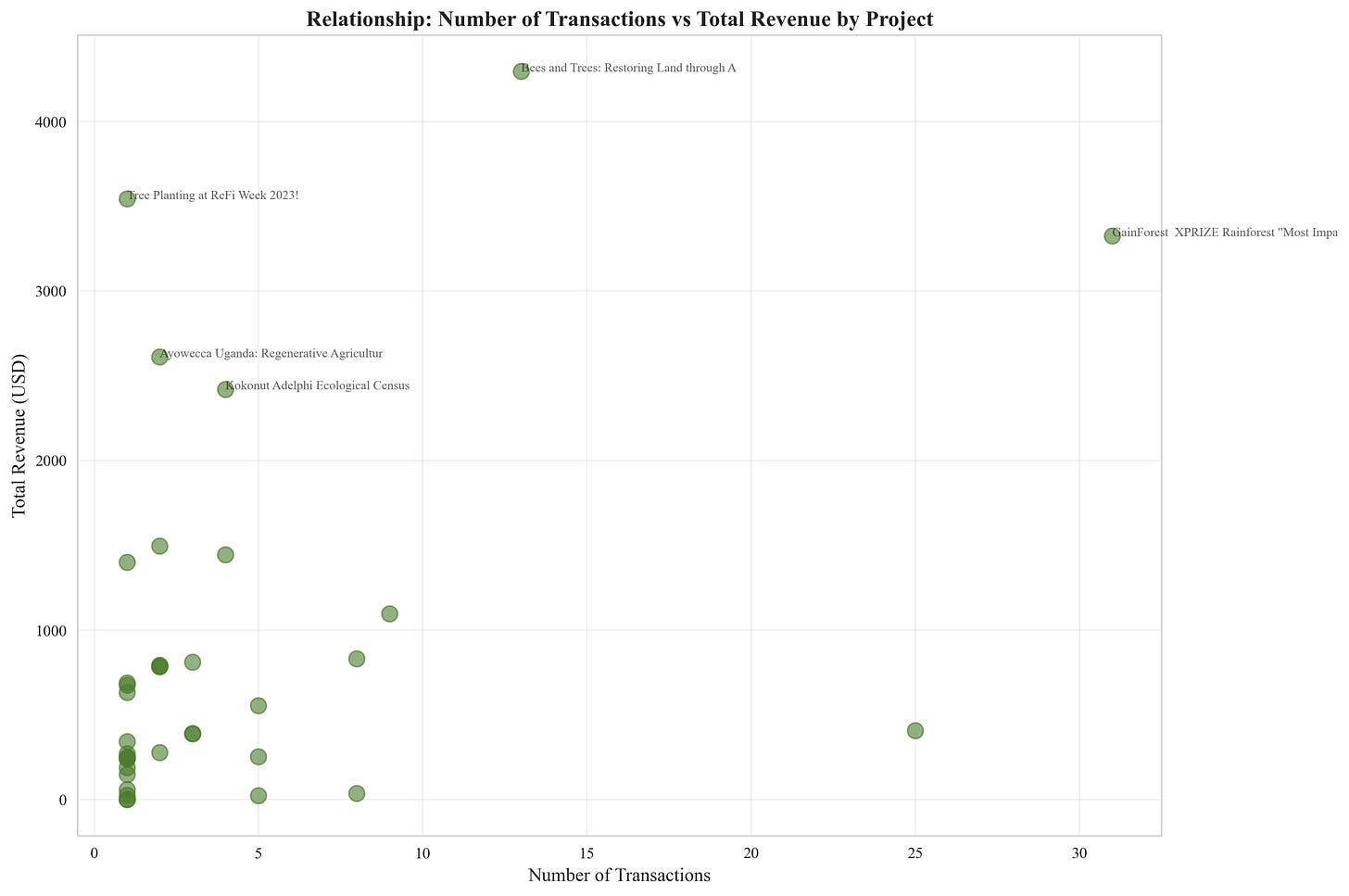

If we look only at the numbers, we see a success story. We analyzed 154 transactions across the initiatives and found a total of 31,724.41 USD in revenue, using a historical CELO price of 0.36 dollars per token. That represents a 264.82% increase from the first month to the last. At one point, there was a single surge that brought 19,046.72 USD into 23 projects in June alone, almost 60% of total revenue.

Underneath this, the pattern is less comfortable. About 70.35% of all contributions came solely from the Hypercerts for Nature Stewards Round we co-hosted in Gitcoin Grants 24. The median contribution across all Bumicerts was 4.96 USD, while the average was 206 USD, with a Gini coefficient of 0.862. In plain language, a small number of contributions and donors account for most of the money. Many projects received almost nothing (Figure 1).

If certification is supposed to be a bridge between community work and resources, that bridge is still standing on a narrow set of pillars. Most Bumicerts income came from a single funding mechanism, in a single window of time, with attention concentrated on a few projects that were already legible to the right audiences.

Funding rounds remain essential mechanisms to amplify contributions to projects. The problem is not their existence, but rather that an approach which relies on a few attention spikes will reproduce inequality. For our team, this means Bumicerts has to move in a different direction, where evidence and funding connect over longer time scales, through multiple channels, and not only during high-visibility events.

What the Data Misses

Bumicerts v1 also gave us a small but revealing laboratory to understand how different types of evidence relate to funding and where those signals collide with deeper structural mismatches.

Some patterns were clear. Projects with richer, more legible evidence tended to receive more contributions. Videos, reports and external profiles made it easier for donors to “see” the work. But what we did not find is just as important. There is no clear evidence that stacking more indicators together, in increasingly complex combinations, leads to proportionally higher funding. The correlation between intricate indicator bundles and contributions is weak and noisy. In practice, the jump from a simple documentation setup to a very complex one increases costs for communities without a guaranteed return.

Meanwhile, the global context makes the stakes obvious. Indigenous peoples and local communities collectively hold or manage roughly half of the planet’s remaining intact forests. They protect enormous carbon stocks and biodiversity, often with far fewer resources than formal conservation programs. Any framework that claims to measure ecological impact but sidelines these actors is incomplete by design.

Data tells you where systems bend. Voices tell you why.

Lydia from the Africa Climate and Environment Foundation (Kenya) wrote to us:

“It’s complex at first, then simple as I navigate the steps. Tracking donations is easy. It feels organized. But yes, improvements would help.”

Her comment captures what we heard often. Bumicerts were “usable,” but clarity was missing. What do they enable? How should evidence look? What makes a “good” Bumicert?

Peter, from Project Mocha (Kenya), added:

“The onboarding was simple, but I wanted more education… curated check-ins… guidance.”

This is not a request for more bureaucracy, but for more shared understanding - a missing ingredient in almost every global certification framework.

Then there is Juliandi from Pandu Alam Lestari Foundation (Indonesia), who leads a project in Kalimantan:

“We attracted donors because the Ecocert system made our claims more trustworthy.”

Their success rate reached 95%. But what came next reveals the real fracture in global systems:

“We had to verify impact data one by one… photos, field reports, statistics… and the website was heavy and slow. In the interior of Kalimantan, the signal is weak. Sometimes the site fails completely when we try to upload from the field.”

Max from Fork Forest (Argentina) surfaced another structural gap:

“Some donors weren’t able to finish a contribution. Choosing the coin confused them.”

In a system meant to expand access to climate finance, even small UX decisions can quietly shut the door.

For Bumicerts v2, our goal is to create a minimal, meaningful set of signals that funding partners can trust, without pushing communities into unsustainable documentation burdens and ensuring both communities and donors understand what is happening at every step.

From Prototype to Ecosystem: Bumicerts v2 in Motion

The Nature Guild is building a governance and learning layer around communities, focusing on cohorts, practice, local leadership and incentives that are not limited to financial rewards. The legacy upload and data platforms already allow communities and partners to send in files, photos, shapefiles, and logs that can be standardized on the backend without overburdening people in the field. BroadListening provides a way to structure, analyze and visualize community data at scale. It can ingest Bumicerts submissions, funding records and external signals, and turn them into transparent, queryable dashboards.

Some projects thrived because they had people who could navigate dashboards, write in English or manage web3 wallets. Others stayed in the margins and only surfaced briefly when a call for projects reached them through a messaging group or personal contact.

The transition from v1 to v2 will be a shift from a prototype to a more coherent ecosystem, and that work is already in progress:

AT Protocol integration in partnership with Hypercerts Foundation is underway, so Bumicerts can live as interoperable, verifiable claims in a broader public-good data layer instead of being trapped in a single platform.

A more comprehensive ecosystem for Nature Guild decisions, eligibility and standards is being designed, coupled with better data-upload experiences like our AI-driven bot Tainá, which helps communities send evidence in formats that are easier to process without demanding technical expertise.

GainForest is preparing a return to Brazil in 2026 for new missions, research and community field work, using our results to shape how we listen, document and co-design with local partners on the ground.

Within this broader infrastructure, Bumicerts v2 will evolve in three directions:

From single events to continuous presence, with a living registry where projects can gradually strengthen their evidence and supporters can contribute at any time.

From “more data” to evidence ladders, with a small number of achievable tiers that are legible to donors.

Lastly, from opaque verification to transparent logic and shared governance, where communities can see how their evidence is interpreted and help define what “good evidence” means in their context through the Nature Guild.

An Invitation, Not a Verdict

We’ve learned that a few honest videos, reports, and web pages can dramatically change how donors respond, but that piling up indicators does not magically solve inequality. Many communities will show up even when the process is imperfect, as long as they feel someone is genuinely listening. Global certification models are still misaligned with the ways people actually protect forests, soils, water and futures at small community scale.

The world of impact certification is built on the assumption that nature behaves in spreadsheets. Communities know it behaves in seasons, failures, improvisation, and relationships. Bumicerts v1 was a mirror showing both the creativity and the impossible barriers that community-led projects face under global rules.

Moving forward, Bumicerts v2 starts from a simple belief: technology, human judgment, and community governance together can do better than one-size-fits-all templates. We’re building a way to see and support the work communities are already doing, in the language of their own landscapes.

Bumicerts v2 is coming soon. Stay connected for updates.

The mismatch between funding concentration and evidence complexity is telling. That Gini coefficient of 0.862 basically means most projects got scraps while a few captured attention. I've worked with similar community forestry initiatives before, and the issue isn't lack of good evidence but the fact that what counts as "legible" is defined by urban-based funders who dunno what satellite-validated tree counts actually mean on th ground. The insight about evidence ladders over complex indicator stacks is spot-on becuase it acknowledges the real constraint is bandwidth, not capability.